A blueprint for large numbers

Consider a modest function “A,” which takes a number and adds one to it.

A ( 1 ) = 2 A ( 2 ) = 3 A ( 99 ) = 100 \begin{aligned}

A(1) &= 2 \\

A(2) &= 3 \\

A(99) &= 100

\end{aligned} A ( 1 ) A ( 2 ) A ( 99 ) = 2 = 3 = 100

It’s not much of an operator, and is easily defeated by its counterpart: “evil A.”

A ˇ ( 2 ) = 1 A ˇ ( 3 ) = 2 A ˇ ( 100 ) = 99 \begin{aligned}

\check A(2) &= 1 \\

\check A(3) &= 2 \\

\check A(100) &= 99

\end{aligned} A ˇ ( 2 ) A ˇ ( 3 ) A ˇ ( 100 ) = 1 = 2 = 99

We can apply “A” multiple times.

A ( A ( 1 ) ) = A ( 2 ) = 3 A ( A ( A ( A ( 1 ) ) ) ) = 5 \begin{aligned}

A(A(1)) = A(2) &= 3 \\

A(A(A(A(1)))) &= 5

\end{aligned} A ( A ( 1 )) = A ( 2 ) A ( A ( A ( A ( 1 )))) = 3 = 5

Repeating “A” is a little tiring, so we can use a superscript to make things a little more concise.

A ( A ( 1 ) ) = A 2 ( 1 ) = 3 A ( A ( A ( A ( 10 ) ) ) ) = A 4 ( 10 ) = 14 \begin{alignedat}{2}

A(A(1)) &= A^2(1) &&= 3 \\

A(A(A(A(10)))) &= A^4(10) &&= 14

\end{alignedat} A ( A ( 1 )) A ( A ( A ( A ( 10 )))) = A 2 ( 1 ) = A 4 ( 10 ) = 3 = 14

Since the superscript implies “add 1 this many times,” the following properties unfold:

A n ( 1 ) = 1 + n A n ( 10 ) = 10 + n A n ( 99 ) = 99 + n \begin{aligned}

A^n(1) &= 1 + n \\

A^n(10) &= 10 + n \\

A^n(99) &= 99 + n

\end{aligned} A n ( 1 ) A n ( 10 ) A n ( 99 ) = 1 + n = 10 + n = 99 + n A n ( m ) = m + n A^n(m) = m + n A n ( m ) = m + n

🔗

Small steps

Our goal is to make large numbers, so we may start throwing some of them at A in hopes of making them even bigger.

A 1000 ( 1000 ) = 2000 A 1000000 ( 1000000 ) = 2000000 \begin{aligned}

A^{1000}(1000) &= 2000 \\

A^{1000000}(1000000) &= 2000000

\end{aligned} A 1000 ( 1000 ) A 1000000 ( 1000000 ) = 2000 = 2000000

But we’re not making much progress. For starters, we have to pass in

two big numbers - what a waste. Let’s not repeat ourselves so much by creating a new function “B”:

B ( n ) = A n ( n ) B(n) = A^n(n) B ( n ) = A n ( n )

Now we can pass large numbers into B just once - half the work (I checked!).

B ( 1000 ) = A 1000 ( 1000 ) = 1000 + 1000 = 2000 B ( 1000000 ) = 2000000 B ( 1000000000 ) = 2000000000 \begin{aligned}

B(1000) &= A^{1000}(1000) \\

&= 1000 + 1000 \\

&= 2000 \\

B(1000000) &= 2000000 \\

B(1000000000) &= 2000000000

\end{aligned} B ( 1000 ) B ( 1000000 ) B ( 1000000000 ) = A 1000 ( 1000 ) = 1000 + 1000 = 2000 = 2000000 = 2000000000

We can see that the following property holds:

B ( n ) = A n ( n ) = n + n = 2 ⋅ n B(n) = A^n(n) = n + n = 2 \cdot n B ( n ) = A n ( n ) = n + n = 2 ⋅ n

Try as it might, “evil A” can’t stop our new friend “B” from taking our numbers to great heights.

A ˇ ( n ) = n − 1 B ( n ) = 2 ⋅ n A ˇ ( B ( 10 ) ) = 20 − 1 = 19 A ˇ ( B ( 100 ) ) = 199 A ˇ ( B ( 5000 ) ) = 9999 \begin{aligned}

\check A(n) &= n - 1 \\

B(n) &= 2 \cdot n \\

\check A(B(10)) &= 20 - 1 = 19 \\

\check A(B(100)) &= 199 \\

\check A(B(5000)) &= 9999 \\

\end{aligned} A ˇ ( n ) B ( n ) A ˇ ( B ( 10 )) A ˇ ( B ( 100 )) A ˇ ( B ( 5000 )) = n − 1 = 2 ⋅ n = 20 − 1 = 19 = 199 = 9999

But “evil B” can, stopping our numbers dead in their tracks.

B ˇ ( n ) = n 2 B ( n ) = 2 ⋅ n B ˇ ( B ( 10 ) ) = 20 2 = 10 B ˇ ( B ( 100 ) ) = 100 B ˇ ( B ( 5000 ) ) = 5000 \begin{aligned}

\check B(n) &= \frac{n}{2} \\

B(n) &= 2 \cdot n \\

\check B(B(10)) &= \frac{20}{2} = 10 \\

\check B(B(100)) &= 100 \\

\check B(B(5000)) &= 5000 \\

\end{aligned} B ˇ ( n ) B ( n ) B ˇ ( B ( 10 )) B ˇ ( B ( 100 )) B ˇ ( B ( 5000 )) = 2 n = 2 ⋅ n = 2 20 = 10 = 100 = 5000

We’ll need something stronger.

🔗

Slightly bigger steps

We have a function “B” which

doubles a number.

B ( 1 ) = 2 B ( 99 ) = 198 B ( 500 ) = 1000 \begin{aligned}

B(1) &= 2 \\

B(99) &= 198 \\

B(500) &= 1000

\end{aligned} B ( 1 ) B ( 99 ) B ( 500 ) = 2 = 198 = 1000

We can apply “B” multiple times.

B ( B ( 1 ) ) = B ( 2 ) = 4 B ( B ( B ( 10 ) ) ) = 80 \begin{aligned}

B(B(1)) = B(2) &= 4 \\

B(B(B(10))) &= 80

\end{aligned} B ( B ( 1 )) = B ( 2 ) B ( B ( B ( 10 ))) = 4 = 80

To shorten things, we can use our trusty friend, the superscript.

B ( B ( 1 ) ) = B 2 ( 1 ) = 4 B ( B ( B ( 10 ) ) ) = B 3 ( 10 ) = 80 \begin{alignedat}{2}

B(B(1)) &= B^2(1) &&= 4 \\

B(B(B(10))) &= B^3(10) &&= 80

\end{alignedat} B ( B ( 1 )) B ( B ( B ( 10 ))) = B 2 ( 1 ) = B 3 ( 10 ) = 4 = 80

This pattern may be a bit harder to spot, but we can handle it by expanding things a little.

B 4 ( 5 ) = 2 ⋅ B 3 ( 5 ) = 2 ⋅ 2 ⋅ B 2 ( 5 ) = 2 ⋅ 2 ⋅ 2 ⋅ B ( 5 ) = 2 ⋅ 2 ⋅ 2 ⋅ 2 ⋅ 5 = 2 4 ⋅ 5 \begin{aligned}

B^4(5) &= 2 \cdot B^3(5) \\

&= 2 \cdot 2 \cdot B^2(5) \\

&= 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot B(5) \\

&= 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 5 \\

&= 2^4 \cdot 5

\end{aligned} B 4 ( 5 ) = 2 ⋅ B 3 ( 5 ) = 2 ⋅ 2 ⋅ B 2 ( 5 ) = 2 ⋅ 2 ⋅ 2 ⋅ B ( 5 ) = 2 ⋅ 2 ⋅ 2 ⋅ 2 ⋅ 5 = 2 4 ⋅ 5

The following pattern emerges:

B n ( 5 ) = 2 n ⋅ 5 B^n(5) = 2^n \cdot 5 B n ( 5 ) = 2 n ⋅ 5 B n ( m ) = 2 n ⋅ m B^n(m) = 2^n \cdot m B n ( m ) = 2 n ⋅ m

Just as before, we’ll consolidate m and n by introducing a new function “C.”

C ( n ) = B n ( n ) = 2 n ⋅ n C(n) = B^n(n) = 2^n \cdot n C ( n ) = B n ( n ) = 2 n ⋅ n

🔗

Getting there

Our numbers are starting to grow pretty quickly:

C ( 3 ) = 2 3 ⋅ 3 = 24 C ( 10 ) = 2 10 ⋅ 10 = 10240 C ( 100 ) = 2 100 ⋅ 100 = 12676506 … \begin{alignedat}{2}

C(3) &= 2^3 \cdot 3 &&= 24 \\

C(10) &= 2^{10} \cdot 10 &&= 10240 \\

C(100) &= 2^{100} \cdot 100 &&= 12676506\mathellipsis

\end{alignedat} C ( 3 ) C ( 10 ) C ( 100 ) = 2 3 ⋅ 3 = 2 10 ⋅ 10 = 2 100 ⋅ 100 = 24 = 10240 = 12676506 …

Passing 100 to our friend “C” produces

126765060022822940149670320537600, which is a whopping 33 digits in length. Switch the 100 to 1000 and we get:

107150860718626732094842504906000

181056140481170553360744375038837

035105112493612249319837881569585

812759467291755314682518714528569

231404359845775746985748039345677

748242309854210746050623711418779

541821530464749835819412673987675

591655439460770629145711964776865

421676604298316526243868372056680

69376000

Coming in at 305 digits. Pretty huge - larger than

the number of particles in the universe - but still easily represented here in this article.

Additionally, our “evil B” from earlier is no match for us now.

B ˇ ( n ) = n 2 C ( n ) = 2 n ⋅ n B ˇ ( C ( 10 ) ) = 5120 B ˇ ( C ( 100 ) ) = 633825 … (32 digits) B ˇ ( C ( 1000 ) ) = 535754 … (304 digits) \begin{aligned}

\check B(n) &= \frac{n}{2} \\

C(n) &= 2^n \cdot n \\

\check B(C(10)) &= 5120 \\

\check B(C(100)) &= 633825\mathellipsis \text{(32 digits)} \\

\check B(C(1000)) &= 535754\mathellipsis \text{(304 digits)}\\

\end{aligned} B ˇ ( n ) C ( n ) B ˇ ( C ( 10 )) B ˇ ( C ( 100 )) B ˇ ( C ( 1000 )) = 2 n = 2 n ⋅ n = 5120 = 633825 … (32 digits) = 535754 … (304 digits)

Try as it might, “evil B” can only occasionally knock a single digit off our numbers.

A new challenger approaches, however, that can take them out using its secret weapon -

the logarithm .

C ˇ ( n ) = lg ( n ) C ( n ) = 2 n ⋅ n C ˇ ( C ( 10 ) ) = 13.321 … C ˇ ( C ( 100 ) ) = 106.643 … C ˇ ( C ( 1000 ) ) = 1009.965 … \begin{aligned}

\check C(n) &= \lg(n) \\

C(n) &= 2^n \cdot n \\

\check C(C(10)) &= 13.321\mathellipsis \\

\check C(C(100)) &= 106.643\mathellipsis \\

\check C(C(1000)) &= 1009.965\mathellipsis \\

\end{aligned} C ˇ ( n ) C ( n ) C ˇ ( C ( 10 )) C ˇ ( C ( 100 )) C ˇ ( C ( 1000 )) = lg ( n ) = 2 n ⋅ n = 13.321 … = 106.643 … = 1009.965 …

Our numbers are

barely able to escape the mighty logarithm. We’ll need something stronger.

🔗

To new heights

We have a function “C” which raises 2 to the power “n” and multiplies it by “n”

C ( n ) = 2 n ⋅ n C ( 3 ) = 2 3 ⋅ 3 = 24 C ( 10 ) = 2 10 ⋅ 10 = 10240 \begin{alignedat}{2}

C(n) &= 2^n \cdot n \\

C(3) &= 2^3 \cdot 3 &&= 24 \\

C(10) &= 2^{10} \cdot 10 &&= 10240 \\

\end{alignedat} C ( n ) C ( 3 ) C ( 10 ) = 2 n ⋅ n = 2 3 ⋅ 3 = 2 10 ⋅ 10 = 24 = 10240

This function has a little sibling which does the same thing, but does not multiply by “n”. It won’t produce numbers quite as big, but will be a little easier for us to work with.

C ˙ ( n ) = 2 n C ˙ ( 3 ) = 8 C ˙ ( 10 ) = 1024 \begin{aligned}

\dot C(n) &= 2^n \\

\dot C(3) &= 8 \\

\dot C(10) &= 1024

\end{aligned} C ˙ ( n ) C ˙ ( 3 ) C ˙ ( 10 ) = 2 n = 8 = 1024

We can apply “little C” multiple times.

C ˙ ( n ) = 2 n C ˙ ( C ˙ ( n ) ) = 2 C ˙ ( n ) = 2 2 n C ˙ ( C ˙ ( C ˙ ( n ) ) ) = 2 C ˙ ( C ˙ ( n ) ) = 2 2 C ˙ ( n ) = 2 2 2 n \begin{alignedat}{2}

\dot C(n) &= 2^n \\

\dot C(\dot C(n)) &= 2^{\dot C(n)} &&= 2^{2^n} \\

\dot C(\dot C(\dot C(n))) &= 2^{\dot C(\dot C(n))} \\

&= 2^{2^{\dot C(n)}} &&= 2^{2^{2^{n}}}

\end{alignedat} C ˙ ( n ) C ˙ ( C ˙ ( n )) C ˙ ( C ˙ ( C ˙ ( n ))) = 2 n = 2 C ˙ ( n ) = 2 C ˙ ( C ˙ ( n )) = 2 2 C ˙ ( n ) = 2 2 n = 2 2 2 n

Just as before, we can use our trusty friend the superscript.

C ˙ 5 ( n ) = 2 2 2 2 2 n \dot C^5(n) = 2^{2^{2^{2^{2^n}}}} C ˙ 5 ( n ) = 2 2 2 2 2 n

Repeated applications of “little C” result in these fairly alien “towers” of 2s. In particular:

C ˙ m ( n ) = 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2 n ⏟ m copies of 2 \dot C^m(n) = \underbrace{2^{2^{2^{\cdot^{\cdot^{\cdot^{2^n}}}}}}}_{\text{m copies of 2}} C ˙ m ( n ) = m copies of 2 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2 n

Once again we can consolidate m and n:

D ( n ) = C ˙ n ( n ) = 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2 n ⏟ n copies of 2 D(n) = \dot C^n(n) = \underbrace{2^{2^{2^{\cdot^{\cdot^{\cdot^{2^n}}}}}}}_{\text{n copies of 2}} D ( n ) = C ˙ n ( n ) = n copies of 2 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2 n

Just as we removed the trailing end for “C”, we’ll remove the trailing n for “D” to simplify things.

C ( n ) = 2 n ⋅ n C ˙ ( n ) = 2 n D ( n ) = 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2 n ⏟ n copies of 2 D ˙ ( n ) = 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2 ⏟ n copies of 2 \begin{aligned}

C(n) &= 2^n \cdot n \\

\dot C(n) &= 2^n \\

D(n) &= \underbrace{2^{2^{2^{\cdot^{\cdot^{\cdot^{2^n}}}}}}}_{\text{n copies of 2}} \\

\dot D(n) &= \underbrace{2^{2^{2^{\cdot^{\cdot^{\cdot^{2}}}}}}}_{\text{n copies of 2}}

\end{aligned} C ( n ) C ˙ ( n ) D ( n ) D ˙ ( n ) = 2 n ⋅ n = 2 n = n copies of 2 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2 n = n copies of 2 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2

These “towers of exponents” are referred to as “

tetrations ” and are typically represented using

Knuth’s up-arrow notation .

D ˙ ( 5 ) = 2 2 2 2 2 = 2 ↑ ↑ 5 \dot D(5) = 2^{2^{2^{2^2}}} = 2 \uparrow \uparrow 5 D ˙ ( 5 ) = 2 2 2 2 2 = 2 ↑↑ 5

They’re bizarre-looking, and grow…

really quickly . How quickly?

D ˙ ( 2 ) = 2 2 = 4 D ˙ ( 3 ) = 2 2 2 = 16 D ˙ ( 4 ) = 2 2 2 2 = 65536 D ˙ ( 5 ) = 2 2 2 2 2 = 2 65536 \begin{alignedat}{2}

\dot D(2) &= 2^2 &&= 4 \\

\dot D(3) &= 2^{2^2} &&= 16 \\

\dot D(4) &= 2^{2^{2^2}} &&= 65536 \\

\dot D(5) &= 2^{2^{2^{2^2}}} &&= 2^{65536}

\end{alignedat} D ˙ ( 2 ) D ˙ ( 3 ) D ˙ ( 4 ) D ˙ ( 5 ) = 2 2 = 2 2 2 = 2 2 2 2 = 2 2 2 2 2 = 4 = 16 = 65536 = 2 65536

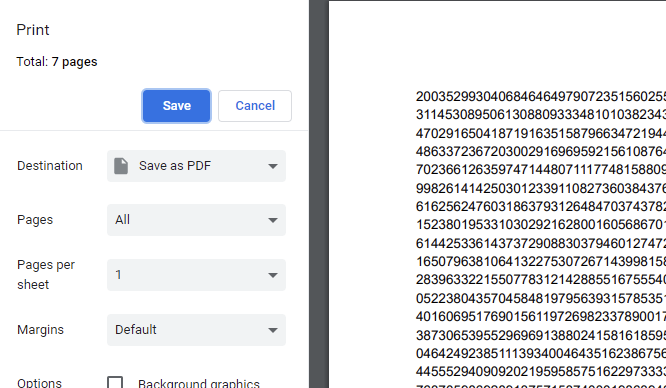

At just 5 items in, we’re produced a number that is 19,729 digits in length. Much larger than anything we’ve seen so far, but still

tangible . In fact, I can print this number at size 11 font with 1" margins in just 7 sheets of paper (about 3,000 digits per page).

a print preview showing the very long number (20035299...) with "Total: 7 pages”

D ˙ ( 6 ) = 2 2 2 2 2 2 = ??? \dot D(6) = 2^{2^{2^{2^{2^2}}}} = \text{???} D ˙ ( 6 ) = 2 2 2 2 2 2 = ???

What

is this number? Concretely, it’s 2 raised to the giant number we just saw. How much larger does that make it?

While we could print

D(5) on 7 pages of paper, we’ll need 7 pages of paper

just to print the number of digits in D(6) . What if we wanted to print

D(6) itself? We’ll need about

D(5) pages.

More specifically, we’ll need

D(5) / 3,000 pages, but

D(5) is so massive the

/ 3,000 does absolutely nothing to it.

How about

D(7)? We’ll need

D(5) / 3,000 pages to print its digits, and

D(6) / 3,000 pages to print the number itself. There’s a pattern here, but not one that translates well into physical sheets of paper. Simply put, the number’s big.

In fact, our function generates numbers so big that “evil C” is quickly drowned by them.

C ˇ ( n ) = lg ( n ) C ˇ ( D ˙ ( 2 ) ) = lg ( 2 2 ) = 2 C ˇ ( D ˙ ( 3 ) ) = lg ( 2 2 2 ) = 2 2 C ˇ ( D ˙ ( 4 ) ) = lg ( 2 2 2 2 ) = 2 2 2 C ˇ ( D ˙ ( 5 ) ) = lg ( 2 2 2 2 2 ) = 2 2 2 2 C ˇ ( D ˙ ( 6 ) ) = lg ( 2 2 2 2 2 2 ) = 2 2 2 2 2 \begin{alignedat}{2}

\check C(n) &= \lg(n) \\

\check C(\dot D(2)) &= \lg{(2^2)} &&= 2 \\

\check C(\dot D(3)) &= \lg{(2^{2^2})} &&= 2^2 \\

\check C(\dot D(4)) &= \lg{(2^{2^{2^2}})} &&= 2^{2^2} \\

\check C(\dot D(5)) &= \lg{(2^{2^{2^{2^2}}})} &&= 2^{2^{2^2}} \\

\check C(\dot D(6)) &= \lg{(2^{2^{2^{2^{2^2}}}})} &&= 2^{2^{2^{2^2}}}

\end{alignedat} C ˇ ( n ) C ˇ ( D ˙ ( 2 )) C ˇ ( D ˙ ( 3 )) C ˇ ( D ˙ ( 4 )) C ˇ ( D ˙ ( 5 )) C ˇ ( D ˙ ( 6 )) = lg ( n ) = lg ( 2 2 ) = lg ( 2 2 2 ) = lg ( 2 2 2 2 ) = lg ( 2 2 2 2 2 ) = lg ( 2 2 2 2 2 2 ) = 2 = 2 2 = 2 2 2 = 2 2 2 2 = 2 2 2 2 2

Try as it might, “evil C” can only knock off a single item from our ever-growing tower of exponents.

A tower of exponents is a real force to be reckoned with.

🔗

But not big enough

We have a function “D” which generates a tower of 2s with a height of “n.”

D ˙ ( n ) = 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2 ⏟ n copies of 2 \dot D(n) = \underbrace{2^{2^{2^{\cdot^{\cdot^{\cdot^{2}}}}}}}_{\text{n copies of 2}} D ˙ ( n ) = n copies of 2 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2

We can apply this function to itself.

D ˙ ( D ˙ ( n ) ) = D ˙ ( 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2 ⏟ n copies of 2 ) = 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2 ⏟ ( 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2 ⏟ n copies of 2 ) copies of 2 \begin{aligned}

\dot D(\dot D(n)) &= \dot D(\underbrace{2^{2^{2^{\cdot^{\cdot^{\cdot^{2}}}}}}}_{\text{n copies of 2}}) \\

&= \underbrace{2^{2^{2^{\cdot^{\cdot^{\cdot^{2}}}}}}}_{(\underbrace{2^{2^{2^{\cdot^{\cdot^{\cdot^{2}}}}}}}_{\text{n copies of 2}})\text{ copies of 2}}

\end{aligned} D ˙ ( D ˙ ( n )) = D ˙ ( n copies of 2 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2 ) = ( n copies of 2 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2 ) copies of 2 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2

In the previous section, we saw how

D(n-1) dictated the

number of digits for

D(n). Well,

D(D(n)) grows not on the level of

exponents , but on the level of the

number of exponents in the tower .

While D(6) was practically impossible to imagine, D(D(6)) is pure nightmare fuel. Let’s continue.

Just as earlier, we can use a superscript to simplify things:

D ˙ m ( n ) = 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2 ⏟ ( 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2 ⏟ ( ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ) copies of 2 ) copies of 2 } m times \left.

\dot D^m(n) = \underbrace{2^{2^{2^{\cdot^{\cdot^{\cdot^{2}}}}}}}_{(\underbrace{2^{2^{2^{\cdot^{\cdot^{\cdot^{2}}}}}}}_{(\cdot^{\cdot^{\cdot}}) \text{ copies of 2}})\text{ copies of 2}}

\right\} \text{m times} D ˙ m ( n ) = ( ( ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ) copies of 2 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2 ) copies of 2 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2 ⎭ ⎬ ⎫ m times

And we can consolidate m and n like so:

E ( n ) = D ˙ n ( n ) = 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2 ⏟ ( 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2 ⏟ ( ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ) copies of 2 ) copies of 2 } n times \begin{aligned}

E(n) &= \dot D^n(n) \\

&= \left.

\underbrace{2^{2^{2^{\cdot^{\cdot^{\cdot^{2}}}}}}}_{(\underbrace{2^{2^{2^{\cdot^{\cdot^{\cdot^{2}}}}}}}_{(\cdot^{\cdot^{\cdot}}) \text{ copies of 2}})\text{ copies of 2}}

\right\} \text{n times}

\end{aligned} E ( n ) = D ˙ n ( n ) = ( ( ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ) copies of 2 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2 ) copies of 2 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2 ⎭ ⎬ ⎫ n times

These towers-of-towers can be hard to read (and harder to write), so we can simplify things a bit using

our previous up-arrow notation .

D ˙ ( n ) = 2 ↑ ↑ n D ˙ ( D ˙ ( n ) ) = 2 ↑ ↑ ( 2 ↑ ↑ n ) D ˙ ( D ˙ ( D ˙ ( n ) ) ) = 2 ↑ ↑ ( 2 ↑ ↑ ( 2 ↑ ↑ n ) ) D ˙ m ( n ) = D ˙ ( D ˙ ( ⋯ D ˙ ( n ) ) ) ⏟ m copies of D ˙ = 2 ↑ ↑ ( ⋯ ( 2 ↑ ↑ n ) ) ⏟ m copies of 2 \begin{aligned}

\dot D(n) &= 2 \uparrow \uparrow n \\

\dot D(\dot D(n)) &= 2 \uparrow \uparrow (2 \uparrow \uparrow n) \\

\dot D(\dot D(\dot D(n))) &= 2 \uparrow \uparrow (2 \uparrow \uparrow (2 \uparrow \uparrow n)) \\

\dot D^m(n) &= \underbrace{\dot D(\dot D( \cdots \dot D(n)))}_{\text{m copies of } \dot D} \\

&= \underbrace{2 \uparrow \uparrow (\cdots (2 \uparrow \uparrow n))}_{\text{m copies of 2}}

\end{aligned} D ˙ ( n ) D ˙ ( D ˙ ( n )) D ˙ ( D ˙ ( D ˙ ( n ))) D ˙ m ( n ) = 2 ↑↑ n = 2 ↑↑ ( 2 ↑↑ n ) = 2 ↑↑ ( 2 ↑↑ ( 2 ↑↑ n )) = m copies of D ˙ D ˙ ( D ˙ ( ⋯ D ˙ ( n ))) = m copies of 2 2 ↑↑ ( ⋯ ( 2 ↑↑ n ))

(and consolidate m and n):

E ( n ) = D ˙ n ( n ) = 2 ↑ ↑ ( 2 ↑ ↑ ( ⋯ ( 2 ↑ ↑ n ) ) ⏟ n copies of 2 \begin{aligned}

E(n) &= \dot D^n(n) \\

&= \underbrace{2 \uparrow \uparrow (2 \uparrow \uparrow (\cdots (2 \uparrow \uparrow n))}_{\text{n copies of 2}}

\end{aligned} E ( n ) = D ˙ n ( n ) = n copies of 2 2 ↑↑ ( 2 ↑↑ ( ⋯ ( 2 ↑↑ n ))

Lastly, we’ll want to get rid of that pesky “n” at the end and create a “little E” just as we did for “C” and “D”.

D ( n ) = 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2 n ⏟ n copies of 2 D ˙ ( n ) = 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2 ⏟ n copies of 2 E ( n ) = 2 ↑ ↑ ( 2 ↑ ↑ ( ⋯ ( 2 ↑ ↑ n ) ) ⏟ n copies of 2 E ˙ ( n ) = 2 ↑ ↑ ( 2 ↑ ↑ ( ⋯ ( 2 ↑ ↑ 2 ) ) ⏟ n copies of 2 \begin{aligned}

D(n) &= \underbrace{2^{2^{2^{\cdot^{\cdot^{\cdot^{2^n}}}}}}}_{\text{n copies of 2}} \\

\dot D(n) &= \underbrace{2^{2^{2^{\cdot^{\cdot^{\cdot^{2}}}}}}}_{\text{n copies of 2}} \\

E(n) &= \underbrace{2 \uparrow \uparrow (2 \uparrow \uparrow (\cdots (2 \uparrow \uparrow n))}_{\text{n copies of 2}} \\

\dot E(n) &= \underbrace{2 \uparrow \uparrow (2 \uparrow \uparrow (\cdots (2 \uparrow \uparrow 2))}_{\text{n copies of 2}}

\end{aligned} D ( n ) D ˙ ( n ) E ( n ) E ˙ ( n ) = n copies of 2 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2 n = n copies of 2 2 2 2 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 2 = n copies of 2 2 ↑↑ ( 2 ↑↑ ( ⋯ ( 2 ↑↑ n )) = n copies of 2 2 ↑↑ ( 2 ↑↑ ( ⋯ ( 2 ↑↑ 2 ))

Conveniently, mathematicians have an elegant way to represent “apply double-up-arrow n times,” and all it takes is adding a third arrow.

E ˙ ( n ) = 2 ↑ ↑ ( 2 ↑ ↑ ( ⋯ ( 2 ↑ ↑ 2 ) ) ⏟ n copies of 2 E ˙ ( n ) = 2 ↑ ↑ ↑ n \begin{aligned}

\dot E(n) &= \underbrace{2 \uparrow \uparrow (2 \uparrow \uparrow (\cdots (2 \uparrow \uparrow 2))}_{\text{n copies of 2}} \\

\dot E(n) &= 2 \uparrow \uparrow \uparrow n

\end{aligned} E ˙ ( n ) E ˙ ( n ) = n copies of 2 2 ↑↑ ( 2 ↑↑ ( ⋯ ( 2 ↑↑ 2 )) = 2 ↑↑↑ n

🔗

Arrows, arrows, arrows

In fact, if we repeat the process we used to generate “B” through “E”:

E m ( n ) = E ( E ( ⋯ ( E ( n ) ) ⏟ m times E n ( n ) = E ( E ( ⋯ ( E ( n ) ) ⏟ n times F ( n ) = E n ( n ) G ( n ) = F n ( n ) H ( n ) = G n ( n ) … \begin{aligned}

E^m(n) &= \underbrace{E(E(\cdots(E(n))}_{\text{m times}} \\

E^n(n) &= \underbrace{E(E(\cdots(E(n))}_{\text{n times}} \\

F(n) &= E^n(n) \\

G(n) &= F^n(n) \\

H(n) &= G^n(n) \\

\dots

\end{aligned} E m ( n ) E n ( n ) F ( n ) G ( n ) H ( n ) … = m times E ( E ( ⋯ ( E ( n )) = n times E ( E ( ⋯ ( E ( n )) = E n ( n ) = F n ( n ) = G n ( n )

All we’re really doing is

adding more arrows .

E ( n ) = 2 ↑ ↑ ↑ n F ( n ) = 2 ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ n G ( n ) = 2 ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ n H ( n ) = 2 ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ n … \begin{aligned}

E(n) &= 2 \uparrow \uparrow \uparrow n \\

F(n) &= 2 \uparrow \uparrow \uparrow \uparrow n \\

G(n) &= 2 \uparrow \uparrow \uparrow \uparrow \uparrow n \\

H(n) &= 2 \uparrow \uparrow \uparrow \uparrow \uparrow \uparrow n \\

\dots

\end{aligned} E ( n ) F ( n ) G ( n ) H ( n ) … = 2 ↑↑↑ n = 2 ↑↑↑↑ n = 2 ↑↑↑↑↑ n = 2 ↑↑↑↑↑↑ n

Eventually the arrows themselves will become unwieldy:

Z ( n ) = 2 ↑ ↑ ⋯ ↑ n ⏟ 25 arrows Z(n) = \underbrace{2 \uparrow \uparrow \cdots \uparrow n}_\text{25 arrows} Z ( n ) = 25 arrows 2 ↑↑ ⋯ ↑ n

Worry not, for we can provide a superscript

to the arrow itself. (Keep in mind that our numbers became

incomprehensibly large 23 arrows ago.)

Z ( n ) = 2 ↑ ↑ ⋯ ↑ n ⏟ 25 arrows Z ( n ) = 2 ↑ 25 n \begin{aligned}

Z(n) &= \underbrace{2 \uparrow \uparrow \cdots \uparrow n}_\text{25 arrows} \\

Z(n) &= 2 \uparrow^{25} n

\end{aligned} Z ( n ) Z ( n ) = 25 arrows 2 ↑↑ ⋯ ↑ n = 2 ↑ 25 n

So, what if we wanted to continue growing the number of arrows?

I’ll leave that to you, dear reader, for I am exhausted.

Thanks for reading :) If you enjoyed this article, you’ll probably love

Graham’s Number and

TREE(3) .